As Lotus’ founder, Colin Chapman, once said, the best way to make a vehicle faster is to “simplify and add lightness.” While this philosophy was originally applied to sports cars and race cars, it holds even more true in the world of aviation, particularly when it comes to airplanes. In the vast expanse of the sky, where three dimensions of space replace the flat tarmac, every ounce counts, perhaps more so than in the world of cars and trucks. To illustrate the power of this concept, we need look no further than the remarkable story of the Grumman F8F Bearcat, a World War II aircraft that was made lighter, faster, and better.

To fully appreciate the Bearcat’s story, it’s essential to understand its manufacturer, Grumman Aerospace. Founded in 1929 by Leroy Grumman in the town of Baldwin on Long Island, New York, the company eventually relocated to its permanent home in Bethpage, New York, in 1937. Grumman Aerospace primarily dedicated itself to meeting the U.S. Navy’s ever-growing demand for piston-engine fighters for their expanding fleet of aircraft carriers. They started with the FF biplane, affectionately known as the “Fifi,” which was the first U.S.-built aircraft with retractable landing gear.

The pinnacle of this biplane lineage was the F3F, the last biplane ever to serve in the U.S. Navy’s carrier operations. From the F3F’s heritage emerged Grumman’s famous “big cat” line of carrier fighters, starting with the legendary F4F Wildcat. Equipped with features like self-sealing fuel tanks and a reliable Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial engine, the Wildcat held its ground admirably against the relentless attacks of Imperial Japan and its Mitsubishi A6M Zero. However, despite its strengths, the Wildcat’s weight and engine power made it less agile in dogfights against the nimble Zeroes.

Many Wildcats fell victim to Japanese Zeroes luring them into steep climbs that the chunky Wildcat couldn’t match. Wildcats often stalled out at the peak of their climb and tumbled back to Earth like sitting ducks. Something drastic needed to be done to counter this threat, leading to the development of the F6F Hellcat in 1943. The Hellcat, larger and more powerful than the Wildcat, used a Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine that made it a formidable adversary, breaking through the limitations that had hampered Wildcats.

Though not as aesthetically pleasing as the P-51 Mustang or the Spitfire, the Hellcat’s kill-to-loss ratio exceeded even those of the more glamorous World War II fighters. As many as 5,000 enemy aircraft fell to the Hellcat’s six M2 Browning machine guns during the war, accounting for an astonishing 75 percent of the U.S. Navy’s aerial victories in the Pacific Theater. By the war’s end, Grumman engineers recognized that the era of piston-engine supremacy in aerial warfare was waning. However, this did not mean they couldn’t extract more performance from the Hellcat’s design.

Years before the master of lightness, Colin Chapman, built his first race car from an old Austin 7, Grumman decided to apply his famous philosophy to their iconic Hellcat. Legend has it that after the Battle of Midway in 1942, a group of Wildcat pilots met with Grumman’s Vice President, Jake Swirbul, at Pearl Harbor in June of that year. They recognized the need for a small, powerful fighter capable of taking off from escort carriers, a task too challenging for the Hellcat. As a secondary requirement, a high horsepower-to-weight ratio became a high priority.

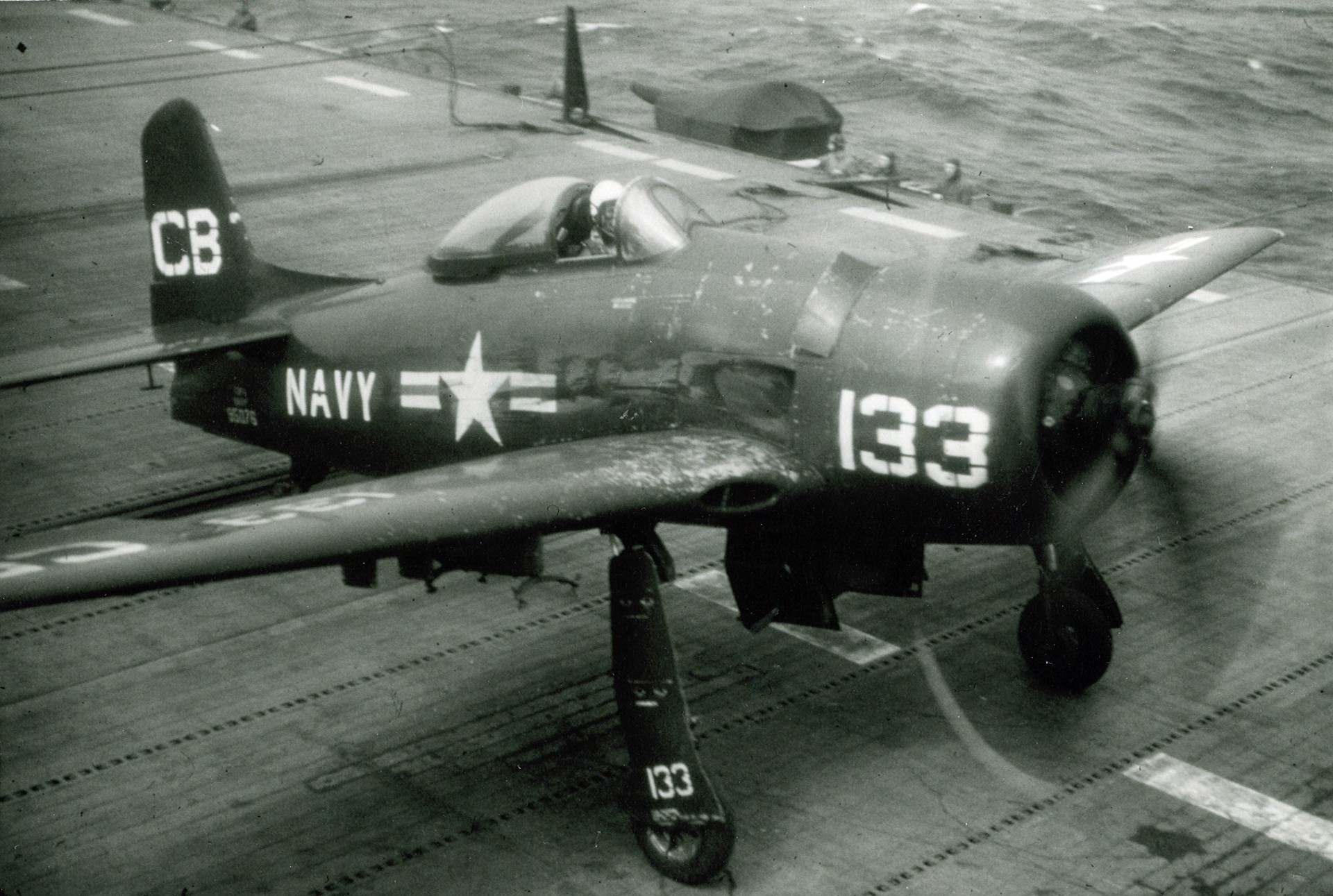

Internally referred to as the G-58, Grumman concluded that the most cost-effective solution for this new fighter was to take the basic architecture of the Hellcat and significantly reduce its size. The Bearcat, as it would later be known, was considerably smaller than the F6F Hellcat, being about 5 feet shorter in length and 7 feet smaller in wingspan. These reductions, along with other weight-saving measures, resulted in the Bearcat being nearly a full ton lighter than the Hellcat. Modifications behind the pilot’s seat allowed for a high-visibility bubble canopy to be installed on each Bearcat, further enhancing its design.

Other weight-saving measures included using four 50-caliber M2 Browning machine guns in the Bearcat’s wings instead of the Hellcat’s six guns and carrying a lighter fuel load of around 183 US gallons. In total, the Bearcat was 20 percent lighter than the Hellcat and about 50 mph faster. On August 21st, 1944, the first prototype XF8F-1 Bearcat took to the skies over Long Island for the first time. In nearly all aspects of flight, the XF8F-1 was a remarkable aircraft. Its climbing abilities could make German Bf-109Ks and late-model A6M Zero pilots envy, even surpassing American planes like the Hellcat and Corsair.

Regarding maneuverability, the Bearcat was akin to a sports car in the sky, with a roll rate that could make even seasoned pilots queasy. Its combat flaps, though not entirely useless, made the Bearcat stand out among carrier-based prop fighters. While Navy fighters were generally considered less robust than their land-based counterparts due to the sturdier airframes required for carrier landings, the Bearcat challenged this notion. Its exceptional performance was evident when a Bearcat set a time-to-climb record, reaching 10,000 feet in just 94 seconds.

On paper, Grumman seemed to have produced a fighter that could take on the air forces of Japan and Germany simultaneously, provided enough of them were manufactured. In terms of raw performance, the only naval prop fighter that came close to the Bearcat was the British Hawker Sea Fury. These two aircraft often vie for the top spot on lists of the best piston-engine fighters ever to take flight.

However, there was a small problem. By the time the Bearcat was ready for deployment on May 21st, 1945, Germany had already surrendered to the Allies two weeks earlier, with Japan following suit in September of that year. Consequently, the Bearcat never saw combat during World War II.

Despite missing its opportunity for wartime combat, the Bearcat remains a significant part of aviation history. A U.S. Navy order for over 2,000 Bearcats resulted in a production run of only 770 airframes. Even replacing the Bearcat’s Browning machine guns with U.S. copies of Hispano Suiza HS.404 autocannons in the F8F-1B variant failed to generate significant interest.

Ultimately, the Bearcat’s shining moment in U.S. Navy service came not in combat but with the Blue Angels aerial acrobatics squadron. Around 200 Bearcats were transferred to the French Air Force in 1951 to assist in the French Indochina War, where the aircraft saw limited combat. A few more Bearcats were provided to Thailand in 1949.

Today, the Bearcat is best known for its participation in air races around the world. Particularly famous is “Rare Bear,” a modified Bearcat airframe equipped with a massive Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone engine, often credited as the world’s most renowned air racer. While the Bearcat never shot down a single Japanese or German aircraft, its achievements in air racing make it impossible to dismiss its significance. In fact, it stands as one of the most important piston-engine fighters of the 20th century.